My brother once emptied a clip at his apartment door—someone

was trying to break it down from the outside. Both parties lived to see another

day, until they didn’t. This is par for the course for heroin addicts. It is

not a lifestyle destined for longevity.

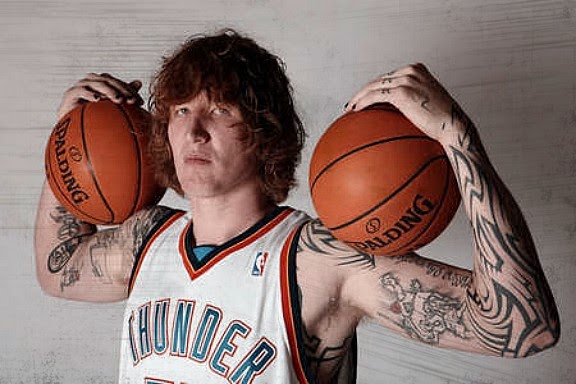

When I read the latest news about Robert Swift—the onetime

center for the Seattle SuperSonics and Oklahoma City Thunder—it seemed like the

logical next drop-step for a basketball curiosity. Because downward spirals are

not complicated patterns. The personalities might be, but not the slide itself—it’s

just a sucking hole and it is rarely denied.

The former NBA prospect pleaded not guilty on weapons charges in a Seattle courtroom Monday. He was arrested January 6, in the town of

Gold Bar, along with 28-year-old Carlos Abraham Anderson. The

inept duo were apparently attempting to rob a home in broad daylight.

As Shari Ireton of the Snohomish County Sheriff’s Office

recounted: “I believe there were a couple of people who called in, they saw

masked subjects on the property, reported that at least one of them was armed

with a weapon, one possibly with a baseball bat. It appeared they were either

trying to make an entry or knocking on the door.”

Gold Bar, Washington—pop. 2,075—began its existence as a

prospectors’ camp in 1889 but more recently faced bankruptcy. Swift, a 7’1”

heavily inked-up dude who averaged 4.3 points per game over an injury-plagued

five-year career in the NBA, earned about $9.8 million as a pro baller. He went

broke a long time ago.

At the time of his arrest, Swift had an outstanding warrant

for failure to appear in court the day after Thanksgiving. The admitted junkie

had initially been arrested October 4, during a SWAT raid, and was charged with

possession of a sawed-off shotgun, along with a grenade launcher and several

other firearms on or under his bed.

Also arrested in the ATF-led operation was his roommate and

owner of the house, Trgve Bjorkstam. Known as “Trigg,” the 54-year-old was

booked for illegal firearms and dealing heroin within 100 yards of the Hellen

Keller Elementary School in Kirkland. Other items confiscated included

methamphetamine, meth pipes, used needles, a blackened fry pan with heroin

residue, and dozens of weapons, some fitted with suppressors.

During their search, agents also discovered a hidden

underground bunker initially used to grow weed before being turned into a

firing range.

According to police reports, Trigg said that the former

hoopster was just a “good guy” who was trying to help him collect on a heroin

debt. There are yet no indications whether the more recent botched robbery was

in any way connected.

***

East Bakersfield is a fairly typical inland community—desert

heat, strip malls and ranch-style houses. Swift grew up as a tall, gangly white

kid, with a younger sister, Samantha, now 22, a brother Alex, 28, and parents

Bruce, 52, and Rhonda, 59. Robert’s dad was an air conditioning repair man who

didn’t work for a few years following a car crash. His mom was dealing with

cancer and seven surgeries. There wasn’t always enough food on the table.

Swift was 6’4” by the time he entered junior high. He did

what super-tall skinny kids usually do and began playing basketball. He got pretty good too, good enough to go to the MacDonald's All American Game, good enough to attract the favor of AAU leeches armed with

promises. Good enough for his parents to encourage pursuing a straight shot

from high school to the NBA.

His high school coach suggested the college path instead. “His body was so frail and if you are seven feet tall at 16, your body has some growing to do,” said Gino Lacava during an interview with the UK Daily Mail. “That NBA schedule is rigorous and it doesn’t take much to hurt you. Me and the other coaches were all thinking the same thing, that Robert had definitely nothing to lose by going to college for a few years.”

But Swift’s parents, described as “middle class at best” by

Lacava, had dollar signs in their eyes. “They got tied in with these AAU

coaches who were constantly throwing around free offers and shoes and all the

money and I think to them…it seemed like free money.”

For Swift, a quiet kid who averaged 20 points, 11 rebounds

and eight blocks per game as a senior, there was the dream of getting lots of

tats, and throwing parties and buying cars. His coaches almost won out

though—Swift committed to playing for USC and Henry Bibby.

But his father hired Arn Tellem at SFX and USC went out the

window. Heading into the draft, Tellem took an unusual approach. Robert wouldn’t attend predraft workouts, wouldn’t talk to teams, wouldn’t take physicals

and wouldn’t attend the Chicago combine. In fact, he wouldn’t even be in New

York City on draft night.

The sports agent didn’t want his client’s weaknesses

exposed.

Bruce revealed the plan at the time, per ESPN: "His

daily routine is to hang out with his buddies and get into some open gyms,

shoot a bit, play against local guys here in Bakersfield."

Absence made the hungry hearts of NBA teams grow fonder—the

skinny kid from the high desert began zooming up draft boards. On June 24,

2004, he was selected as the 12th overall pick by the Sonics.

The Swift family soon left Bakersfield, courtesy of an

18-year-old meal ticket in a custom pinstripe suit. Their ship had finally come

in and the timing couldn’t have been better—Bruce had filed for bankruptcy in

1999 and again in 2003.

That summer trip may have been the best part of what would

ultimately become Robert Swift’s long losing streak.

He earned $1.6 million for his rookie season, minus agent

commission, taxes and other sundry expenses. He leased a Cadillac Escalade EXT

pickup with a 3,500-watt sound system and bought his parents a pair of new SUVS

for Christmas. He also bought them a home in Seattle’s upscale Sammamish

suburb. And he rented himself an apartment near the team’s facility and started

growing his hair and acquiring tattoos.

He didn’t play much basketball, though. Nate McMillan was the head coach at the time and had little patience for the new teenaged

center—the paint was already packed with Jerome James, Danny Fortson, Vitaly

Potapenko, and Nick Collison who had been drafted the year before but sat out

his rookie season with injuries.

McMillan banished Swift to the weight room and told him to

bulk up. The kid complied dutifully and also got more tats, threw parties for

local college kids, began collecting guns and visited his family a few times a

week. When the team went out on the road, Swift’s dad would usually tag along.

Bruce never held a job during his son’s time in the NBA.

During his rookie season, Swift averaged 0.9 points and 0.3

rebounds in 4.5 minutes per game, over 16 games.

McMillan left after 19 years with the Sonics organization in

order to join the Portland Trail Blazers. Bob Weiss was promoted from assistant

coach to head coach for all of 17 games and was then fired. Bob Hill—the man

with the year-round tan—was the next Sonics assistant to take over the lead

chair.

Hill saw something in Swift and began giving him floor time.

He also showed him tough love and tried preparing him for a career in

basketball and life beyond.

Jayson Jenks for the Seattle Times wrote about Swift’s

flameout and the relationship he built with Hill. During summer workouts, the 19-year-old

gushed about a Dodge pickup he had just purchased.

“Robert, I don’t give a (expletive) what your truck looks

like or what you drive,” said Hill. “I’m more concerned about making you better

here so you can get another contract and maybe another, so by the age of 28 or

29 you can be finished in life. That’s my concern. Not your truck.”

Those words would ultimately be prophetic, although not in

the way Hill had hoped.

Swift played his best basketball in the NBA that season,

starting 20 out of 47 games and averaging 6.4 points, 5.6 rebounds and 1.2

blocks per game. He had improved his strength and his footwork, could hold his

own in the post and had a nice feathery touch on mid-range jumpers, converting

50 percent of his shots from 10-to-16 feet.

The Sonics renewed Swift’s contract for his third season.

Hill was planning on making the 20-year-old his starting center for the 2006-07

season. Swift even purchased his own house that July in Sammamish—a sprawling

four-bedroom home valued at $1.3 million. Life was starting to look pretty

rosy.

But during the preseason, Swift dived out of bounds for a

loose ball and tore his right ACL. He wound up missing the entire season. For

all intents and purposes, Swift’s NBA career was over but it would take a couple

more years for the final nail to be driven into his basketball coffin.

Swift gained weight during his year off, got more tattoos

and partied hard at his new mansion. Hill was fired over the phone at the end

of the season, after a 31-51 record and failing to make the playoffs for the

second year in a row.

The Sonics exercised their option to bring Swift back for

another season. He tried making a comeback under new head coach PJ Carlesimo

but appeared in only eight games before wrecking his knee again.

The Seattle franchise had been going through their own

painful transition since changing ownership from Starbucks founder Howard

Schultz in 2006. The team eventually relocated to Oklahoma City as the Thunder,

leaving longtime fans in the Pacific Northwest with a bitter taste.

In July of 2008, Swift signed a qualifying offer with the

Thunder for $3.6 million. It was a bump up from his previous salary by nearly a

million bucks, and would make him a restricted free agent the following spring.

It would also allow a draft bust who had played just 71 games in four years,

one last opportunity to make good.

The kid from Bakersfield was now 22 years old. He was big

and had a body covered in black ink, and had begun painting his fingernails

black as well. He was lugging a bulky knee brace up and down the court, but had

also dedicated himself to losing weight. He was used sparingly—playing spot

minutes for a few games, sitting out a lot more.

Swift averaged 3.3 points and 3.4 boards in 26 games his

final NBA season. Carlesimo was fired after going 1-12, and Scott Brooks took

over. It was a team heading in a new direction, and that direction would not

include a redheaded center who had once been compared to Bill Walton.

Swift was now a free agent and without a paycheck for the

first time since high school. He played for the Boston Celtics in summer league

action, averaging seven points and 3.6 boards over five games. Danny Ainge had

once coveted the teen prospect and had promised to pick him at No. 15 in the

2004 draft. But Seattle got there first.

Summer league ended without an offer and Swift returned to

his eastside home in the Seattle outskirts. He began drinking heavily and

getting high again. He put the weight back on, plus some. He wandered down to

Bakersfield that fall and began hanging out with old friends.

Swift decided to give his hometown another try. In December,

he signed with the Bakersfield Jam in the D-League. But after just two games he

headed back to Seattle, citing personal issues with his family. The former

lottery pick had also just learned his girlfriend was pregnant.

In July of 2010, Bob Hill was with his son Casey in Dallas,

working out some prospects. Hill had just landed a job coaching Tokyo Apache.

The Japanese pro basketball team first formed in 2004, had been purchased in

June by a Los Angeles-based investor group led by Evolution Capital Management.

Hill contacted Swift, and wanted to know if he’d like to

play some ball again. The season would begin in September. Swift grabbed at the

chance for some semblance of redemption and was also intrigued by the

setting—his paternal grandmother was Japanese. He booked a flight to Texas and

arrived weighing 335 pounds and sporting a Mohawk.

He told Bob and Casey he’d get a haircut and lose the

weight. He’d get right.

But when the season began in Japan, Swift had trouble

adjusting. He’d lost 70 pounds of mostly water weight but hadn’t gotten his

timing or his confidence back yet. There were things that were bothering him.

According to Jenks and the Seattle Times, Bob and Casey

walked into the troubled center’s darkened Japanese apartment in December. He

was alone and hung over in bed, an empty vodka bottle nearby. His fiancé had

phoned to call off their engagement.

Bob Hill told Swift to get out of bed and read him the riot

act: “Maybe being drafted at the age of 18 wasn’t fair. Maybe making all that

money at that age wasn’t the right thing for you. But it happened and you have

to deal with all this. You’re going to have to plant your feet on the ground

and take control of your life.”

Swift began to cry. And then he began putting himself back

together. He stopped drinking and worked on his game. He turned 25 and began

collecting double-doubles—something that had occurred only twice during his

entire time in the NBA. He also mentored 19-year-old Jeremy Tyler—another

cautionary tale who skipped college.

The transformation was so dramatic that NBA scouts

started calling. The Celtics and New York Knicks wanted to bring Swift in

for workouts when his season was done. Hill said it was fun to watch somebody

turning their life around.

On March 11, 2011, a massive 9.0 earthquake occurred in the

Pacific Ocean, 231 miles northeast of Tokyo. The shock was so big that it

shifted the earth on its axis and caused 130-foot waves, including a tsunami

that washed out entire cities.

That was the end of the basketball season for Tokyo Apache,

and for their existence altogether. The L.A. investors decided it just wasn’t

worth it and scuttled the enterprise.

***

Swift returned to his home in Sammamish. In April, he worked

out for the Portland Trail Blazers. A brief YouTube video of a tall, slim

ginger with a wispy beard shooting jumpers may be the last known basketball

footage of the former McDonald’s All-American.

On July 1, 2011, the NBA went on a lockout. It lasted five

long months. It wasn’t a good time for a basketball reclamation project to be

wishing for a job.

Instead, he started putting harm in his arm and stopped

paying the mortgage on his house. Nearly $10 million had slipped away over the

years. It would take another 12 months before the bank finally foreclosed on

the property.

Swift began shutting down and shutting people out—people

like Bob and Casey Hill, like his old coach Lacava, like childhood friends from

Bakersfield, and even some members of his own family.

In text exchanges with the UK Daily Mail, Robert’s mother

said she hadn’t spoken to him in years, adding: “He bought and did things for

his dad and sister but not for his brother or me.”

She also mentioned a book she was writing that would “tell

the whole truth.” Because a tell-all book deal will certainly explain how

parents helped a multimillion dollar meal ticket grow into a broke heroin

addict with a bunch of guns under his bed.

The foreclosure on the house in Sammamish wasn’t a quick and

tidy affair. Swift, who owed more than $160,000 in back payments did not want

to leave his home. He just wanted to be left alone—with his friends and his

dogs and a girlfriend, and his gun collection and various cars in the yard including

an El Camino without an engine.

And so he became a squatter in the house he bought with NBA

money and then that became the Robert Swift story—for another nine months. He

stayed there even after a young couple bought the house at 50 cents on the dollar

in January of 2013.

Once the media outlets got hold of the story, little bits of

information became malleable. The former draft bust became “Seattle’s

basketball savior” and the $10 million he earned turned into $20 million. One

local news anchor with a stentorian voice described Swift as the “No. 1 overall

draft pick.”

And everybody wanted to know how it came to this.

The nice young couple tried calling Swift and writing

letters and knocking on the door of the house they now owned but couldn’t move

into. They hired a lawyer and filed legal charges and did TV interviews. News

crews tried peeking in the windows.

And finally, one weekend at the beginning of March, Swift

and his girlfriend and their dogs were gone. But they left almost all their

belongings behind.

The nice young couple rolled in a giant dumpster almost as

tall as the house and invited a news crew to come and film. And they wrinkled

their noses at the filth as the cameras rolled.

“A lovely way somebody lives,” said the young husband.

"The first thing you get when you walk in the door is kind of whiff of

whatever is festering in here,” said the young wife.

But what else were they supposed to do? They paid their

money just as Swift had paid his. And they wanted to fill their new house with

things they had purchased, just as the onetime basketball prospect had done.

The TV footage and the photo galleries from mainstream

outlets to basketball blogs showed a myriad of images and some were shown more

frequently than others.

There were guns and bullets and empty shell casings. There

were bullet holes in the walls and windows and foundation. An article mentioned

100 pizza boxes and 1,000 beer and liquor bottles. Did somebody actually take

the time to count?

The empties included dozens of cardboard 18-packs of Coors

Light, and there was Mountain Dew and Coca Cola and Twister Tea as well. And

cupcakes squashed on the granite kitchen breakfast bar, and outside there were

blackened hot dog buns by the grill. There were beds and clothes and a bathroom

with blow dryers and toothpaste, and a towel on the vanity that looked like it

had simply been used and left before someone headed out for the day—as if they

might be coming back later. There was a pool table and computers and stereo

equipment, and speakers that once pumped out music, loud and strong. And board

games and a model of a covered wagon and a large fishing net and a graveyard of

remote controls. The basement had been turned into a firing range and the deck

was a place for dogs to poop.

And then there were the photographs of an all-too-short NBA

career, and photos of Bakersfield. And a box of letters from colleges with

scholarship offers. And outside was a brightly painted basketball court that

unlike the interior of the house, seemed oddly clean and well-cared for.

After Swift left, and the dumpster got filled to

overflowing, the stories began to recede into the background. Few people seemed

to know or care where a washout had wandered off to. Casey Hill said the last

he heard, the former basketball player was working as a salesman somewhere in

Seattle.

Eight months passed and another NBA draft came and went, as did

another summer league. And a new NBA season began and there were new draft

busts to write about.

And then the stories came flooding back. A guy who admitted

to doing heroin every day got popped in a drug den 100 feet away from an

elementary school and didn’t show up for his hearing. And a month later he

turned up in a small town that had fallen off the map.

How do you end a downfall story about a homeless seven-foot

junkie who decides to put a stocking over his head and knock on someone’s door

in Gold Bar?

With a convenient tag about hope for brighter days ahead, or

an improbable return to a profession that never quite worked out? Swift’s

basketball career didn’t have to end when the earth shifted on its axis and a

giant wave hit the Japanese coastline.

He could have played for dozens of other teams that provide

refuge and employment for NBA outcasts. But a house and guns and dogs and pizza

boxes, and bindles of heroin, were infinitely warmer and easier.

By the time Swift was arraigned on possession of a sawed-off shotgun Monday, he looked frailer than any time since high school. He is being represented by the King County department that works with indigent defendants. His next court date will be January 26.

By the time Swift was arraigned on possession of a sawed-off shotgun Monday, he looked frailer than any time since high school. He is being represented by the King County department that works with indigent defendants. His next court date will be January 26.

Ultimately, we look at stories through the lens of our own

existence, and sometimes seminal journeys and family memories. Like a string of

bullet holes stitched in an apartment door, left by someone who died long ago.

This one is for you my brother.

(updated 1/12/15)

(updated 1/12/15)

Great article, Dave, what a sad, sad, story.

ReplyDelete